What is Experience Design? And how does it help make things better?

We’re drowning in labels. How can we get back to basics with Experience Design?

In our rush as product, service and experience improvers, it’s easy sometimes to get lost in the detail. We sprint out of the gate to do great research, draw experience maps, construct prototypes, test ideas and release pilots into the world. But it’s worth taking a moment to remember, albeit briefly, what Experience Design is, what it isn’t, and how it helps us make things better (and make better things).

This won’t be a deep review of the topic. For that, you can sample some of Christopher’s work over on Adventures in a Designed World, where he explores Human Factors, Instead, let’s just set the scene for why we at Cognitive Ink do, and promote, Experience Design.

Experience Design has its roots in several overlapping fields, including: Ergonomics, Human Factors, Human Centred Design, Human Computer Interaction, Usability, Information Architecture, User Experience (UX) and User Interface Design (UI).

Some of these terms, like Ergonomics, stretch back centuries. The concept coined by naturalist Professor Wojciech Jastrzebowski in the 1800s with ‘Ergonomy,’ a term that was improved by Human Factors pioneer Hywel Hurrell in 1949 as ‘Ergonomics.’ The words are a fusion of the Greek ‘Ergon,’ for ‘Work’ and ‘Nomos,’ for ‘Natural law’. Put them together and we get ‘the natural laws of work’. Americans have long preferred the term ‘Human Factors,’ but they amount to the same thing.

Other terms, like ’Human Computer Interaction,’ emerged in the 1950s and 1960s, with the rise of the new digital interfaces that would come to dominate our world. ‘Experience Design’ comes from ‘User Experience Design,’ coined by psychologist and design luminary Don Norman in 1988.

It’s a panoply of terms, but don’t worry, we’ll be sticking with Experience Design to keep things simple.

But before we go further, there’s a twist here.

We could argue that you can’t really design an experience. After all, an experience is something people have. It emerges from people interacting with people, technology, and process.

So, you can’t really design an experience directly, but we can, and do, design the channels, interfaces, processes, content, training policies, business models and other ‘things’ that make up the experience. In doing so, we make it more likely people will have a quick, high-performing, effective or pleasurable expeirence. Our criterion for success may change, depending on what the experience is. You want a visit to the dentist to be quick and a luxurious dinner to be long.

So what is Experience Design?

Experience Design is both a philosophy, method and a collection of tools for researching and designing the overall experience an individual (or group) has with (or within) a product, service, environment, procedure, organisation or even entire culture. Experience Design seeks to improve our experiences by changing things to make them better for people, rather than forcing people to adapt to the things we make.

This is based, in part, on the ISO standard definition of Human Centred Design,

“Human-centered design is an approach to interactive systems development that aims to make systems usable and useful by focusing on the users, their needs and requirements, and by applying human factors/ergonomics, and usability knowledge and techniques. This approach enhances effectiveness and efficiency, improves human well-being, user satisfaction, accessibility and sustainability; and counteracts possible adverse effects of use on human health, safety and performance.— ISO 9241-210:2019(E)”

It also draws a little from Don Norman’s original definition of User Experience, "User experience" encompasses all aspects of the end-user's interaction with the company, its services, and its products.” And also a little from an original definition of Human Factors:

“Human factors focuses on human beings and their interactions with products, equipment [etc.]… Human factors, then, seeks to change the things people use and the environments in which they use these things to better match the capabilities, limitations and needs of people.” (Sanders and McCormick, 1992)

Note the distinctions in our definition.

It’s about changing things first, to suit people. Rather than training people to be contortionists and work around the constraints or limitations of technology. In its inception, Expeirence Design leans heavily on social science, humanities and design to create a philosophy and process used to make things better and make better things.

Experience Design typically starts with or supports people, which is why it’s sometimes known as Human Centred Design. That said, the root concept, ‘Experience,’ could just as well apply to any life-form on the planet.

Given how humans continue to be the primary change agents in our world, solving broad environmental problems probably has to start with understanding humans. We are the ones who will exacerbate problems with our individual and mass behaviour, or solve them with our group efforts. Designing a better world for polar bears will still involve all the people that contribute, shape or impinge on a polar bear’s existence.

Making things better is the goal of Experience Design, but that doesn’t mean it’s about always shaping things just to be easy. Sometimes, we might want something to be a little harder to do. Like when managing someone’s experience with an everyday software application on their computer. Imagine designing a workflow where they carry out a full-scale delete operation. You’d have to be careful with that task. We wouldn’t want it to be too easy to delete your entire music library, would we?

‘Better’ isn’t always necessarily just subjective aesthetics, though aesthetics (how things look) are part of making things easier to use. Instead, Experience Design explores a wide range of performance improvements, including:

Increased Usability and Comfort

Higher Desirability and Aesthetics

Better Outcomes and Satisfaction

Better Safety, Reduced Errors, Error recovery

Reduced Stress

Increased Value, etc.

‘Better’ also doesn’t always apply to the improvement of an existing experience. Sometimes we design things that will never exist, or help form plans for future construction.

That’s often the best time to bring in Experience Design, before the first keel-plank is laid. Through research, storytelling, mapmaking and design, we can explore what something should look like before significant expenditure has been made or risky designs become disasters in a live environment.

Is Experience Design the only form of design intervention?

Hardly.

There are many sub-disciplines within the broader envelope of Experience Design, including: Service Design, User Interface Design, Training Design, Content Design and more. Sitting ‘Above’ Experience Design are the broad, macro-scale design approaches of Culture Formation, Systemic Design and Systems Thinking. At the widest scale of society and built environment, there’s policy professionals, urban planners, city, region or state officials.

There’s a lot of groups that have a vested interest in trying to make better products, services and systems for a wide range of people. Experience Design is one among many, but it has several key ‘super-powers.’

First, Cross-domain Pollination – because Experience Designers usually work across domain, they can apply insights and successes from one domain into another. Allowing new ways of being effective to pollinate across an array of experiences.

Second, Social Science Backing—Effective Experience Designers should have a strong combination of social science skills (e.g. psychology, anthropology, sociology etc.) and design training, which means they understand people and how design can meet people’s needs, capabilities and constraints.

Third, Technology Agnostic—Experience Design is based on a technology-agnostic approach to solutions. It’s like that expression, ‘To the child with a hammer, the entire world is a nail.’ Many other disciplines working to make a change in the world often have an allegiance to one type of intervention; be it digital technologies, policies, economic incentives or changes to the built-environment. When faced with a current state, it’s harder for them not to resort to a familiar technology to solve it.

In contrast, Experience Designers draw maps, tell stories and build prototypes for any number of interactions, mediums and technologies. So they’re more free to dream up future solutions that cross boundaries, mix technologies, or where appropriate, set aside high technology in favour of face-to-face human services.

Fourth and finally, Macro-but-practical Scale—Moving up into the most abstract levels of design, like Systemic Design, can produce interesting macro-level insights about complex problems, like housing, healthcare or education. However, from such a high-level perspective, it can be hard to tease out practical design interventions that can make change.

In contrast, Experience Design ventures far up into a birds-eye view of a complex system; it is still a macro-scale perspective. But, because it constantly pushes down to moments of interaction, it is more inclined to produce concrete interventions that can be organised into short, medium and long-term implementation.

Experience Design makes change easier.

What are the outputs of Experience Design?

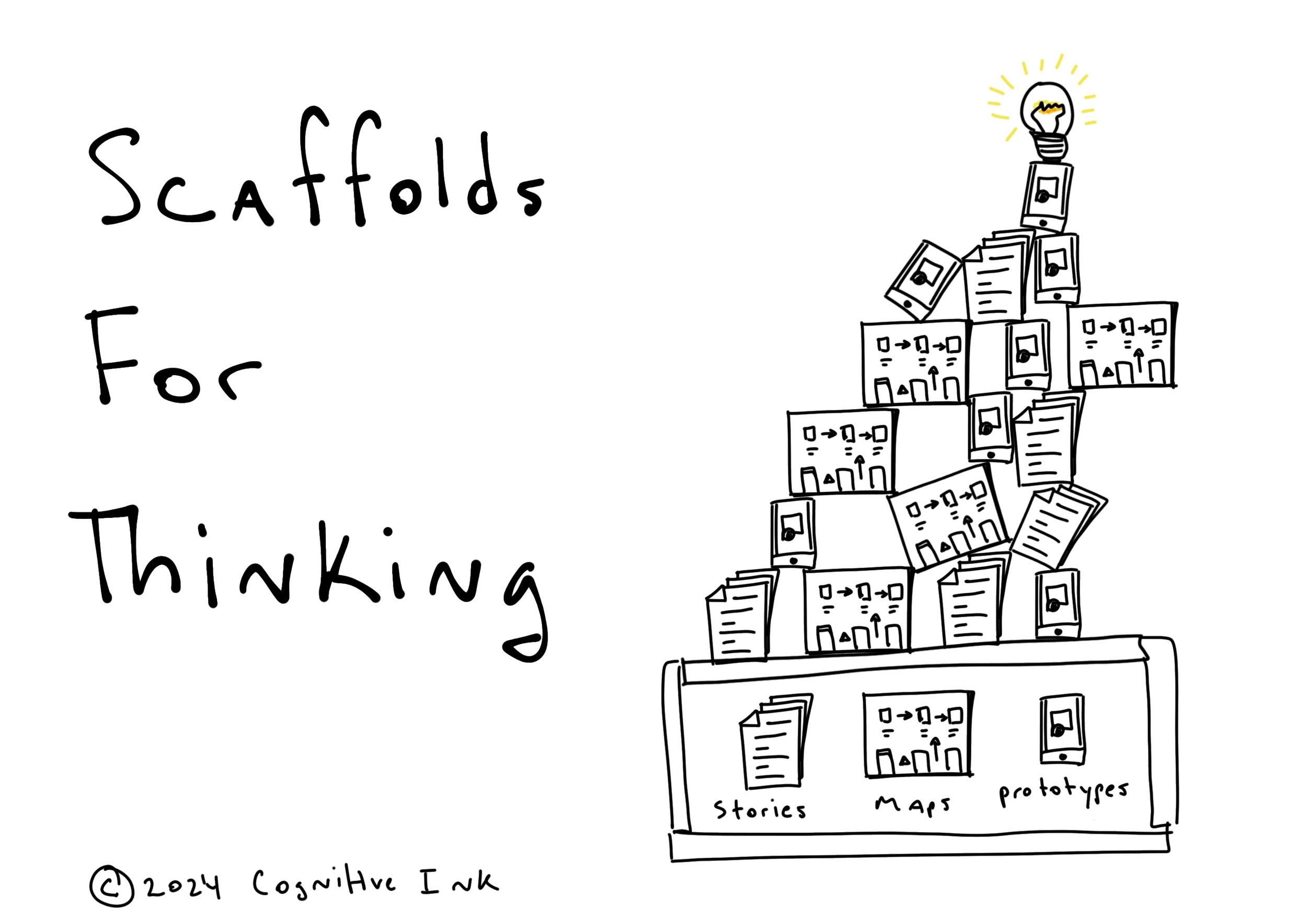

The outputs of Experience Design can take many forms. Usually, they involve a story, map, or prototype. Either focused on how the experience works now, or how it could work in the future.

These stories, maps or prototypes are sometimes called ‘Scaffolds for Thinking,’ because they help teams think about what good looks like, what should be avoided and how to get from where we are now to where we want to be.

These interventions lead the charge into new or improved experiences, but they don’t carry the work all the way to detailed design and build. That’s where specialists take over from the detailed design and construction disciplines that bring products and services of all kinds to life.

Remember, Experience Design isn’t experience engineering or product and service construction. It’s an interstitial (in-the-middle) discipline that helps paint a vision which carries entire teams through to a better product, service, policy, procedure, technology or environment.

What happens if we skip Experience Design?

Just don’t.

Need a few examples?

Q. Ever heard of Chernobyl?

A. If you haven’t, it was a terrible critical failure at a nuclear power plant that contaminated much of Europe in the 1980s. The cause of which was traced to a mixture of poor interface design–a plant control room that didn’t communicate effectively to its users, and a failure of training procedure.

Q. Have you heard about the Challenger disaster?

A. This was another critical failure of the NASA’s space shuttle program, where the Challenger shuttle burned up on launch when a booster failed. The cause was traced to poor information display and decision-making procedures that led to the launch of a spacecraft when conditions weren’t suitable.

Q. Do you know why the iPhone succeeded and other mobile phone products of the time failed?

A. Because Apple invested in a revolutionary user interface, app store framework and branding; creating a mobile phone experience that redefined an entire industry.

Obviously, the first two examples are really serious. They’re what we call ‘Mission Critical’ systems that failed and people died. Because they were critical systems, the responsibility for designing the organisational structures, workflows, services, control interfaces, information systems, decision-making frameworks, training procedures would have probably fallen on a mix of human factors and human centred design specialists.

The third example is less of a critical failure and more of an innovation failure. Nokia and all the other phone manufacturers of the time failed to understand the importance of the mobile device experience, possible new modes of interaction and radical experience features. In doing so, they lost the innovation race.

Whether you’re dealing with a critical system or not, you’re better off doing the right thing.

Invest in quality Experience Design early and use its outputs as the crucial ‘Scaffolds for Thinking’ to guide you down the path to a better product, service, or experience. It makes for better things and a better experience for your users, customers, employees and citizens.

References

https://www.nngroup.com/articles/definition-user-experience/

ISO 9241-210:2019(E) – https://www.iso.org/standard/77520.html

Sanders, M. S., & McCormick, E. J. (1993). Human Factors in Engineering and Design (International). McGraw-Hill International.

The Gaumont-Palace cinema, place de Clichy by Louis Abel-Truchet - Public Domain - https://www.rawpixel.com/image/2909787/free-illustration-image-paris-cinema-oil-painting